Shimon Dzigan was born in Lodz, Poland. A place of poverty, Lodz was filled with colourful characters, and Dzigan, with his outstanding talent, knew how to express their unique humour. He was one of the first young actors in the “Klein Kunst Theater” established by the poet Moshe Broderzon.

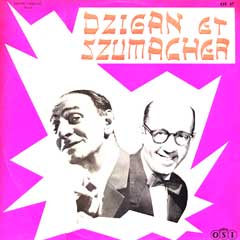

Later he joined the “Ararat” Yiddish Theatre, and after it was closed teamed up with Israel Shumacher, to form the most famous Yiddish comic duo “Dzigan and Shumacher”.

Shimon Dzigan and Yisroel Schumacher were the last of a dying breed. A talented comedy duo, they were the last masters of Yiddish comedy created for a Yiddish-speaking audience. This was a centuries-old tradition which grew up in Eastern Europe only to be cut short in the second half of the 20th century. By the end of their career together, the world the two had grown up in had disappeared as had, more or less, their language.

Dzigan and Schumacher were recently highlighted as part of a documentary series on Israeli humor and entertainment. Their story would make a great screenplay: a pair of funny, talented fellows who got caught up in the wheels of history.

In the beginning they were two young guys from Lodz who wrote and performed skits. Schumacher played straight man to Dzigan’s rubber-faced clowning. Together, they were a kind of Yiddish Abbot and Costello. (In fact, one of their most famous sketches, “Einstein Weinstein”, plays a lot like “Who’s on First”). They performed on stage, they made films. They became superstars among the huge Jewish population of Poland and Eastern Europe. Life was good.

And then the Nazis came.

The Germans invaded Poland and the Jews of Lodz were rounded up into a ghetto. Dzigan and Schumacher continued to perform their skits, using the Nazis and their henchmen as a rich source for contemptuous humor. But Lodz became increasingly dangerous. When an opportunity to escape came, they took it.

D&S fled eastwards to the Soviet Union. Initially, they were given a warm welcome and continued their performing careers. Unfortunately, the two never caught the hang of what one was permitted and forbidden to say in Stalin’s Russia. After one too many cracks about the Great Man, the pair were sent to a labor camp in Siberia.

They sat out the rest of the war in the Gulag. A year or two after the fighting was finished, they were released and returned to Poland. What they found there has been documented in the 1948 film Unzere Kinder (“Our Children”).

The movie is a strange mix of narrative and documentary. Dzigan and Schumacher return to Lodz to perform for a group of children who survived the Holocaust. In the course of this, the kids act out their experiences during the war.

This idea has the potential of turning into a painful shmaltz-fest. (I shudder to think what Robin Williams would do with the same material.) But somehow, it manages to avoid becoming an exercise in pathos, mainly because the children on screen are actual survivors telling their own stories.

Unzere Kinder was one of the first movies to confront the issue of the Holocaust, and would be one of the last for several decades afterwards.

Having survived both Hitler and Stalin, D&S came to Israel in the early 1950s. In the Land of the Jews, they could finally perform their material without hassle. Or so they thought. Sadly, they ran into one of the most unpleasant aspects of Israel’s early years: the drive to impose a specific national culture on all the citizens.

One of the hallmarks of Zionist movements was the revival of Hebrew from being a language used only in prayers to a language used in everyday discourse. It is a remarkable achievement, but it had an ugly flipside. Alongside the resurrection of Hebrew, there was a nationalistic drive to stamp out the use of other languages. (The rallying cry was “ivri, daber ivrit” — “Hebrew person, speak Hebrew!”).

The majority of the new immigrants didn’t speak Hebrew. They mainly spoke Yiddish or Arabic. They — and especially their children — were made to feel embarrassed about this. As a result, the children stopped speaking Yiddish even though they still understood it. Their children would not know the language at all. (This is less true for Arabic, but that’s another story altogether).

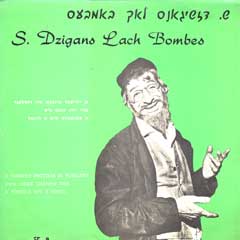

This drive for Hebrew exclusivity had a legal component. In a piece of irony fit for Sholem Aleichem, the young Jewish state had laws severely curtailing performances in Yiddish. Dzigan and Schumacher played a cat-and-mouse game with the authorities coupled with extensive legal battles.

After a while, they got tired of this game and moved to Argentina. There they once again became superstars among the large Jewish immigrant population. Eventually, the duo came to a compromise with the authorities in Israel. They would continue to perform their skits, but they had to include a certain percentage of material in Hebrew. They agreed to this despite the fact that neither of them ever learned the language very well.

And so it went. In the early 60s, they had a falling out. The comedy partnership, which had held together through the worst of times, came to an end. Schumacher died a few years later. Dzigan continued to perform. (He had a television show here in the ’70s, which goes to show how far we’d progressed by then.) One night, he suffered a heart attack on stage in the middle of a performance. He cracked jokes all the way to the hospital where he passed away.

The world that Dzigan and Schumacher came from — the Ashkenazi culture of Eastern Europe — no longer exists. To a great extent, the same holds true for the language they worked in. Today, most native speakers of Yiddish are either octogenerians or members of the ultra-orthodox enclaves of Brooklyn and Mea Shearim.

Although there has been a revival of interest in the language over the last 10 years, it is likely to remain a museum piece at best. In its shortsighted desire to create a national culture, Israel helped kill off the language Jews used for everyday conversation for over a millenium. And that’s a damned shame.

Dzigan used to end his television shows by paraphrasing e.e. cummings. “Remember,” he would say, “a day without laughter is a wasted day.” Like many other things, it sounds a lot better in Yiddish.

After Shumacher died , Dzigan went on performing until his own death in 1980.

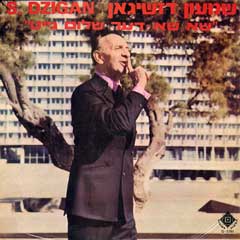

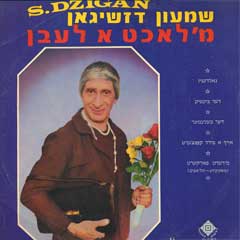

25 Songs Performed by Shimon Dzigan

-

4 Vokhen Nokh Der Khasene2:57

-

4 Yuren Nokh Der Khasene4:54

-

A Heylung Far Di Nerven9:22

-

A Porfolk Mit A Hintl8:54

-

A Rendl a Vort8:44

-

A Yiddisher Protzess in Russland14:03

-

Del Oleh Shanghai11:44

-

Der Astronaut11:23

-

Der Bitnik14:08

-

Der Bloys Vays Telefon5:29

-

Der Khelemer7:14

-

Der Milioner12:06

-

Einshtein Weinshtein12:39

-

Goldenyu9:54

-

Merdt Farkehrt4:30

-

Oi Ala ikh lig in adama2:04

-

Oyf a Fidl Concert9:28

-

Tzvei Moshes In Ein Miklat8:14

-

Tzvei Yidn Khapen Fish9:49

-

Untergheherter Telefon Cairo - Rabat-Aman10:01

-

Vifl Ir Farshteyt12:38

-

Yankel Katzev14:48

-

Yiddishe Ghesheftn9:20

-

Yidn Forn Kayn Yisroel7:51

-

Zol Zayn Sholem12:01