Yiddish Classical Music In America

There is a saying that a language is a dialect with an army and a navy. Yiddish, the historic language of Central and East European Jewry, never had either and suffered miscategorization as a jargon and corruption of German. On the contrary, Yiddish is an extraordinarily rich language with a remarkable literary and folk culture. It is a fusion of medieval Germanic dialects with Hebrew and Aramaic, and components drawn from other language families as well. It is written with the Hebrew Alphabet (from right to left), has its own grammar, and a variety of regional dialects.

Despite the incredible richness of this language, for most of its 1,000 year history, it was not a language of high literary or artistic output. Until the late 19th century, most upwardly mobile Jews writing secular poetry and novels did so in the majority languages of the co-territorial cultures within which they lived, like German, Polish, Russian, and English. However, in the late 19th century there was a decisive turn with the intention of elevating Yiddish language and culture, led by writers like Mendele Moykher-Sforim (pen name of Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh), Sholem Aleichem (pen name of Shalom Rabinovitz), and Y. L. Peretz, by actively creating literary works in Yiddish, which was the language that the majority of world Jewry spoke at the time.

In 1908 a musical organization was founded in St. Petersburg with a similar impetus. Students at the conservatory in St. Petersburg were learning about the national Russian music of composers like Glinka, Mussorgsky, and their teachers who included Rimsky-Korsakov, as well as the national music of other countries. Motivated by a mixture of philosemitic encouragement to explore their Jewish identity, as well as antisemitic discouragement that kept them from feeling fully Russian, Jewish students of the St. Petersburg conservatory banded together to create what became known as the The Society for Jewish Folk Music.

The organization was committed to fostering a new national Jewish school of composers. Just as Béla Bartók worked as both an ethnomusicologist and a composer, collecting folksongs and then infusing his music with them, so too did the composers of this organization and a wider community around it. They supported the collection and study of Jewish folksongs and wrote, published, and performed classical music which sought to craft a new style drawing inspiration from Jewish folk melodies, the music of klezmer musicians, nigunim, and Jewish liturgical music. While engaging with Jewish folk music was at the core of their organizational activity, some of their songs and compositions endeavored to be Jewish by telling stories taken from Jewish religious texts, history, and secular literature, or by turning to poems in Jewish languages such as Hebrew and Yiddish.

The Society and the international network of sister organizations and publishing houses it created nurtured a group of fascinating composers, some of whom stayed in Russia and elsewhere in Europe, like Mikhail Gnessin (1883-1957), Alexander Krein (1883-1951), Moses Milner (1886-1953), and Alexander Veprik (1899-1958), and many of whom emigrated, primarily to British mandate Palestine, like Joel Engel (1868-1927) and Joachim Stutschewsky (1891-1982), and to the United States, like Solomon Rosowsky (1878-1962), Jacob Weinberg (1879-1956), Joseph Achron (1886-1943), Lazare Saminsky (1882-1959), and Leo Zeitlin (1884-1930).

In Russia, which became the Soviet Union, support for Jewish art briefly flourished but then fell precipitously, and many composers involved in explicitly Jewish work were suppressed and at times persecuted. In Palestine conditions were difficult, and many composers who spent time there–including Achron, Saminsky, Rosowky, and Weinberg–eventually made their way to the U.S.A. The composers who stayed in Palestine primarily (though not entirely) shifted to Hebrew as a language for Jewish culture, contributing to the strand of Jewish national renewal that led to the State of Israel and its musical traditions. More recently Yiddish has enjoyed renewed interest in Israel.

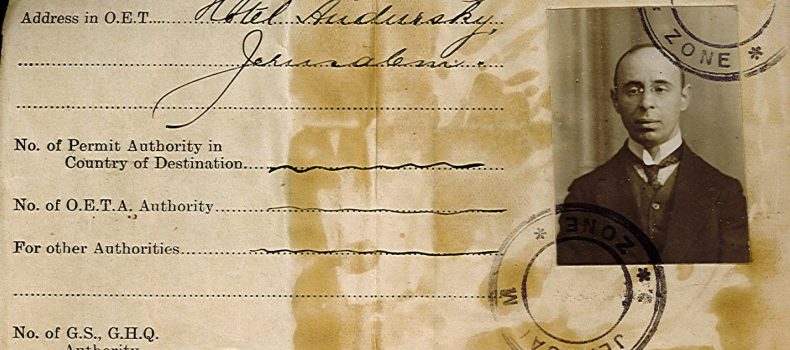

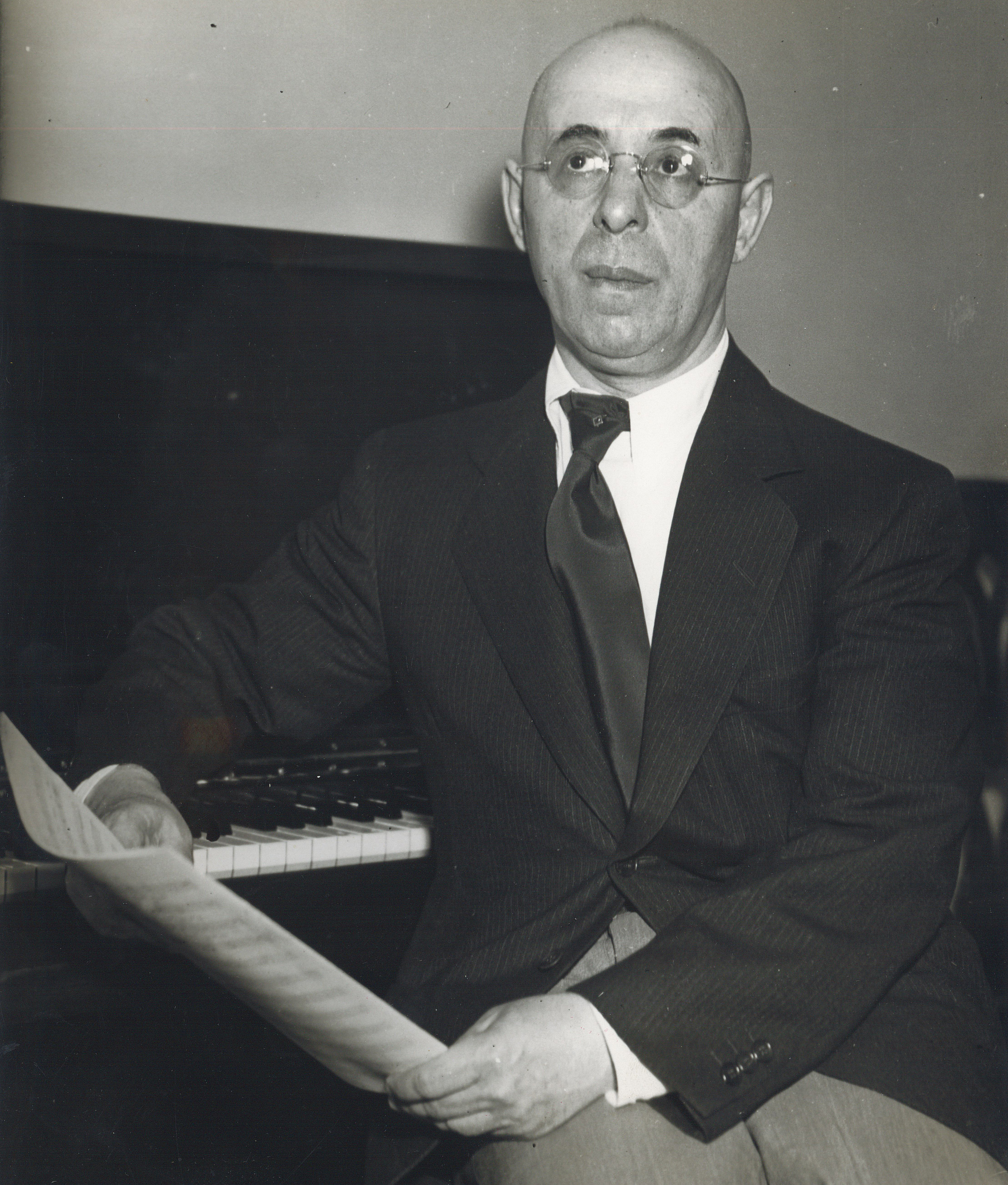

In the U.S. these emigre composers integrated into American musical culture with some notable successes. Saminsky co-founded the League of Composers, Mailamm, and the Jewish Music Forum, and was the music director of Temple Emanu-El from 1924-1958. Rosowsky taught at the Jewish Theological Seminary and published a major work on biblical cantillation. Zeitlin arranged compositions for NBC Radio Network’s flagship station. Weinberg produced performances of his Hebrew language opera Hechalutz at Carnegie Hall in 1946 and 1949. Achron, whom Arnold Schoenberg called “one of the most underrated modern composers,” enjoyed career successes including premiering his first violin concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1927 under the baton of Serge Koussevitsky, premiering his second and third violin concertos–the third commissioned by Jascha Heifetz–under the baton of Otto Klemperer conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Despite all of these successes, the process of immigration and adaptation to the shifting circumstances of the interwar and postwar periods ultimately ruptured the movement that the Society began. There was never again such a centralized and robust support for Jewish art music, and along with it Yiddish song. However, the St. Petersburg Society composers and those of its network were not the only composers who became interested in setting Jewish language poetry to music. Independently of the society, Lazar Weiner (1897-1982, the father of composer and pianist Yehudi Wyner), became interested in Yiddish poetry, writing over 100 Yiddish art songs–all in the United States, after his emigration at age 17. While the Society composers often looked towards folk texts and texts of the early poets of modern Hebrew poetry and Yiddish’s golden age, Weiner set a wide array of the next generation of great Yiddish poets from Yehoash, Joseph Rolnick, Mani Leib, and Moshe Leib Halpern to Jacob Glatstein, Aaron Glanz-Leyeles, and more.

Though Weiner started in isolation from the Society, he encountered their music when the Zimro ensemble toured the U.S. with works by the Society’s composers in 1919. Weiner subsequently sent songs to Joel Engel for advice and became acquainted with many of those composers. One of the major differences in Weiner’s compositional approach is that he was adamantly not interested in quoting folk music. Engel noted that Weiner’s early songs had little “Jewish” content outside of their Yiddish texts, and though Weiner did incorporate some influences of Jewish traditions in his songs, it was never through quotation. More than Jewish folk music, his style brings to mind classic lieder writing and, as Yehudi Wyner has noted, a style similar to Mussorgsky and Debussy in how closely it cleaves to the inflections, stresses, and durations of the texts he set.

Many other emigre composers unaffiliated with the Society also wrote Yiddish songs including lesser known composers such as Janot Roskin (1884-1946), Solomon Golub (1887-1952), Henech Kon (1890-1970), and Maurice Rauch (1910-1994), writing in a range of musical styles that included quasifolk and musical theater, at times blurring the line between popular song genres and lieder. Beyond the world of “Yiddish composers,” many well known American composers dabbled in Yiddish song from Leonard Bernstein to Stefan Wolpe, and Yehudi Wyner to Ofer Ben-Amots. Most recently Bang on a Can composers David Lang and Julia Wolfe have been turning to Yiddish: Lang in two choral works i lie (2001), a re-setting of a folklorized Joseph Rolnick poem, and a girl (2017), a setting of a folksong text; and Wolfe in a movement of her epic chorus and orchestra work for the New York Philharmonic Fire in her mouth (2019), which includes an inventive and gripping fantasy on a Yiddish folksong about sewing.

One of the common threads in all of these composers is that like the writers who kicked off the golden age of Yiddish literature, writing in Yiddish–whether primarily, or occasionally–was for all of them a choice, not a necessity, as every single one of these composers knew/knows a language other than Yiddish, and in most cases numerous other languages. The fact that writing in Yiddish was not a necessity for any of these composers adds a special quality to this body of work. In all of these pieces, the choice of language itself is a compositional one which says something about what the composers were trying to do with their music: connect with Yiddish folk culture, open a window into the Jewish past, or engage with the Jewish literary canon.

A personal note: I decided to use Yiddish in my song cycle and all the days were purple (which became the centerpiece of my debut album of the same name released by Cantaloupe Music in April) as a way to connect with my heritage and contemplate what it means to me. I found in setting Yiddish poetry to music a variety of ways that history, language, and culture can provide access to a rich lineage of which I’m proud to be a part, and a particularly personal way to contribute to the art song genre.

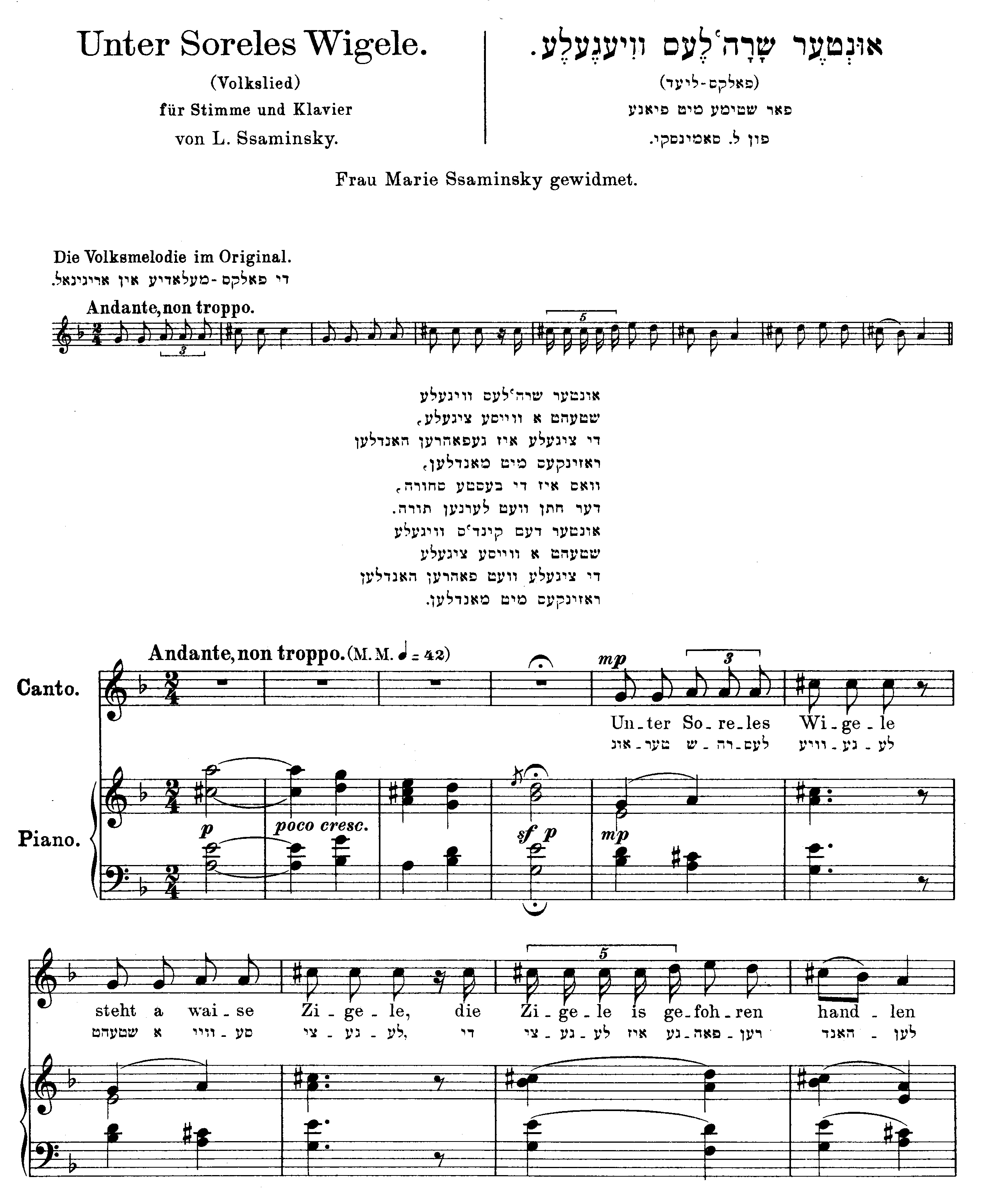

A page from the sheet music for Lazar Saminsky’s song “Under Little Sarahs Cradle,” opus 12 no.2, published in 1914.

Learn More

Spotify Playlist:

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/2jdNcMsoQHfZ32mzVzLw4F

Online Resources:

http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org

http://www.musica-judaica.com/musica_judaica_e.htm

Books:

Loeffler, James: The Most Musical Nation: Jews and Culture in the Late Russian Empire

Song Books:

Heskes, Irene: Society for Jewish Music in St. Petersburg: for voice and piano

Weiner, Lazar: The Lazar Weiner Collection. Book 1, Yiddish Art Songs, 1918-1970

Recordings:

Schneiderman, Helene / Nemtsov, Jascha: On Wings of Jewish Songs

Leo Zeitlin: Yiddish Songs, Chamber Music, and Declamations

Joel Engel: Chamber Music and Folksongs

Solomon Rosowsky: Chamber Music and Yiddish Songs

Milken Archive: Weiner: The Art of Yiddish Song

Milken Archive Digital Volume 9, Album 1: The Art of Jewish Song – Yiddish and Hebrew

Milken Archive Digital Volume 9, Album 2: The Art of Jewish Song – Yiddish and Hebrew