Preview: Stutschewsky’s 13 Jewish Folk Tunes

In the framework of the JMRC project dedicated to the life and work of cellist, composer, researcher and pedagogue Joachim-Yehoyachin Stutschewsky (1891-1982) we are glad to launch an online world-premiere recording of Stutschewsky’s forgotten work 13 Jewish Folk Tunes by cellist and researcher Racheli Galay and composer and pianist Amit Weiner. This early work from 1924 shows Stutschewsky’s exposure to Central European modernism embedded within a Jewish multi-ethnic scene that includes liturgical, para-liturgical and folk tunes of Eastern European and Babylonian Jewish communities. Program notes on the genesis of this work, musical analysis of the composition, and an extensive biographical article will accompany this recording to be released in the JMRC series Contemporary Jewish Music.

Racheli Galay, cello

Amit Weiner, piano

Recorded at Givat Washington Academic College of Education, Mizmor Studio*

Sound technician: Itzik Weiss

Mix and mastering: Harel Hadad

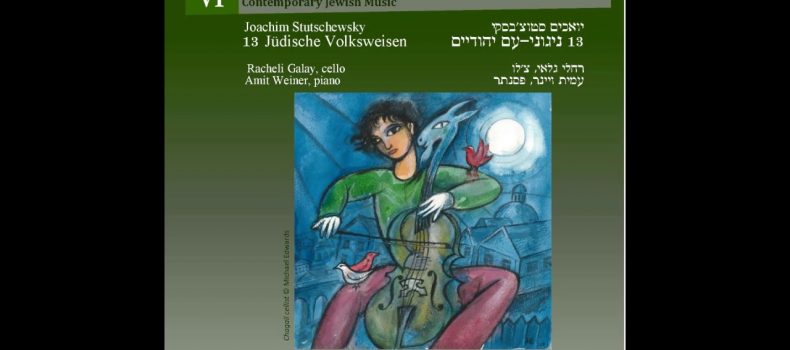

Image on cover: Chagall cellist © Michael Edwards, reproduced by kind permission of Robin Aitchison and Sarah Mnatzaganian www.aitchisoncellos.com

*World premiere recording

No. 11 Zhok

This particular zhok makes a lively climax within the album. Notably, the piano’s part evokes the rhythmic ostinato in the klezmer band. On this triple meter klezmer genre Stutschewky wrote in his comprehensive pioneer book in Hebrew, Ha-Klezmerim, Toldotehem, Orah Hayekhem ve Yezirotekhem ]Klezmorim – History, Folklore, Composition]: “The Zhok was performed especially as a Gas-nigun , and rarely did it serve as accompaniment to a dance. It originated in Moldavian and Romanian music. It entered the klezmer repertoire to a substantial degree and several pieces in the Zhok spirit are named after famous klezmorim.”

No. 8 A Nigun on a soff (chassidisch) – A Tune without Ending (Hassidic)

This piece is the most dissonant and emotionally charged one in the album. It is a hassidic nigun similar to one used by Solomon Rosowsky (1878–1962) in his Nigun on a ssof for Woodwind Quintet, op. 8, no. 2 from 1917. Stutschewsky’s arrangement is marked klagend (lamenting) and indeed it reflects a somber and tense interpretation. “We may say that the hassidic nigun has no beginning and no end” stated Stutschewsky in his book Folklor Musikali shel Yehudei Mizrah-Eiropa. However, this idea of Stutschewsky may extend beyond the hassidic context. The never-ending hassidic nigun streams over a constant sway of dissonant superposed sevenths chords in the piano. This tense relation between melody and accompaniment may be interpreted as a reflection of the friction between the eternal ideals of Judaism and the harsh realities of modern existence.