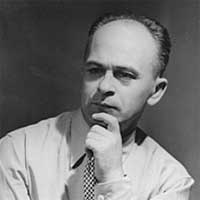

The poet, partisan fighter and eminent collector of the Yiddish Shoah song, Shmerke Kaczerginski was born in 1908 in Vilna, Russian Lithuania. Raised in a Jewish orphanage, he apprenticed in his teens as a printer-lithographer, a vocation that suited his growing passions both for literature and (through access to tools of propaganda) radical politics. Kaczerginski’s activism on behalf of Communist causes, after Vilna’s annexation by the new Polish Republic in 1922, earned him repeated beatings from the police and a spell in prison. The mid-1920s saw the appearance of his first political song, ‘Tates, mames, kinderlekh’ (Fathers, Mothers, Children; also known as “Barikadn” Barricades), a catchy and seditious tune that circulated anonymously within Poland and throughout the Yiddish-speaking world.

In 1929 Kaczerginski joined the Yiddish literary and artistic group Young Vilna, whose members would also include writers Chaim Grade and Avraham Sutzekever. For the next ten years, until Young Vilna’s dissolution at the start of World War II, he served as that influential group’s main organiser, editor and publicist. Under the terms of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact, Vilna became the Lithuanian capital after Poland fell to German armies in September 1939. Less than two years later, Germany turned on its Soviet ally and invaded the Baltic States, stepping up in the process its campaign to eradicate European Jewry. In Vilna, as in all newly-conquered eastern territories, Jews not murdered outright were forced into ghettoes or sent to labour camps. Kaczerginski posed as a deaf-mute to evade the initial round-ups but was ultimately caught and sent to the ghetto in early 1942. Once there, he immediately turned his organisational and versifying skills to the cause of resistance, crafting songs to console and encourage the ghetto prisoners while drawing up schemes to defeat the Germans.

Kaczerginski played a key role in the ghetto’s cultural life, organising theatrical productions, literary evenings, and educational programs. Many lyrics he wrote at this time, notably ‘Friling’ (Springtime; an elegy on the death of his wife), and ‘Shtiler, shtiler’ (Quiet, Quiet) became instant ghetto favourites, as did the anthem he created for the Ghetto Youth Club, ‘Yugnt himn’ (Hymn of Youth). Reflecting on the creation and diffusion of music in such a bizarre environment, he later wrote:

In ordinary times each song would probably have travelled a long road to popularity. But in the ghetto we observed a marvelous phenomenon: individual works transformed into folklore before our eyes.

Soon after arrival, Kaczerginski became actively involved in the ghetto resistance movement. Forced to assist the Nazi effort to plunder Vilna’s rare books and Judaica, he, Sutzkever, and others formed the so-called “Paper Brigade”, whose mission was to smuggle cultural artifacts from the “Aryan side” of Vilna, past armed sentries, and into the ghetto. At about the same time he also joined the United Partisan Organization (Fareynikte Partizaner Organizatsye or FPO), the ghetto’s corps of underground fighters. Throughout this anxious period, Kaczerginski continued to write new songs, believing these might help his fellow prisoners cope with their ever-uncertain situation. He had also begun to suspect that these songs of heroes and martyrs, of everyday life and death during the German occupation, might one day serve to document the history he was witnessing firsthand.

Following the unsuccessful partisan uprising of September 1943, during which the FPO commander was captured and killed (an incident chronicled in the ballad ‘Itsik Vitnberg’), Kaczerginski withdrew from the ghetto together with other members of his battalion. He spent the remaining months of the war in the forested borderlands between Lithuania and Byelorussia, serving first with the FPO, later with a Soviet partisan brigade. It was in his capacity as brigade historian that he began noting down the stories and songs of his comrades-in-arms. In August 1944, he participated in the Soviet liberation of Vilna, and soon set to work locating and salvaging Jewish books, artworks and other cultural artifacts. Disillusioned with the Soviets, however, he left Lithuania for Lódz, Poland, only to move again, after the 1946 Kielce pogrom, to Paris. From this new base, he toured Occupied Germany, lecturing to survivors in Displaced Persons Camps, always continuing to gather new material. The topical songs he now wrote, among them ‘Geshen’ (It happened, about the Exodus incident), ‘Khalutsim’ (Pioneers) and ‘Zol shoyn kumen di geule’ (Redemption will come soon), speak to the plight of Jewish refugees and the hope for a renewal of Jewish cultural and spiritual life.

After the end of the war, Kaczerginski sought to publish the repertoire he had rescued and compiled. In 1947 he contributed a section of ghetto and partisan songs to the anthology Undzer gezang (Our Song), the first Jewish songbook printed in post-war Poland. That same year his edition of Yiddish songs and poems from Vilna, Dos gezang fun vilner geto (The Song of Vilna Ghetto), was published in Paris. Kaczerginski’s best known book, the landmark anthology Lider fun di getos un lagern (Songs of the Ghettoes and Concentration Camps), appeared in New York in 1948. Comprising some 435 pages with 233 songs and poems, this volume remains an indispensable point of reference for research in the field of Jewish folk and popular music of the Holocaust period.

Having remarried in Lódz and begun a family in Paris, Kaczerginski, in 1950, chose to settle in Buenos Aires, where he maintained a hectic schedule writing for newspapers, lecturing about ghetto life, partisan warfare and the Soviet situation, and tirelessly campaigning on behalf of Jewish culture. A popular speaker, he often travelled to engagements in the U.S., Canada and Latin America. It was on the return journey from a speaking engagement in a provincial town that Kaczerginski, age 45, lost his life when his plane crashed in foothills of the Argentine Andes, in April 1954. He left a considerable literary legacy: Khurbn vilne (The Destruction of Vilna; 1947), a chronicle of Vilna during the German occupation; Tvishn hamer un serp (Between Hammer and Sickle; 1949), a polemic on the Soviet repression of Jewish culture; and two combat memoirs, Partizaner geyen! (Partisans Advance!; 1947) and Ikh bin geven a partizan (I was a Partisan; 1952). Above all, with the anthology Lider fun di getos un lagern Kaczerginski made good his promise to preserve and commemorate the tenacious creativity of a people facing genocide. More than fifty years after his death, this work continues to influence new generations of scholars and performers.

12 thoughts on “Kaminos”

Was Nicholas related to Alexander Saslavsky who married Celeste Izolee Todd?

Anyone have a contact email for Yair Klinger or link to score for Ha-Bayta?

wish to have homeland concert video played on the big screen throughout North America.

can organize here in Santa Barbara California.

contacts for this needed and any ideas or suggestions welcomed.

Nat farber is my great grandpa 😊

Are there any movies or photos of max kletter? His wife’s sister was my stepmother, so I’m interested in seeing them and sharing them with his wife’s daughter.

The article says Sheb recorded his last song just 4 days before he died, but does not tell us the name of it. I be curious what it was. I’d like to hear it.

Would anyone happen to know where I can find a copy of the sheet music for a Gil Aldema Choral (SATB) arrangement for Naomi Shemer’s “Sheleg Al Iri”. (Snow on my Village)?

Joseph Smith

Kol Ram Community Choir, NYC

Shalom Joseph. I just saw your 2024 post by chance… I’m a mostly-retired Israeli journalist and translator. In 2003 I translated into English the content (the objective was to remain true to the meaning, not to cadence or rhyme) of poems and lyrics of 48 of Israel’s most iconic songs arranged by Aldema for choirs abroad singing in Hebrew (the words in the scores are transliterated) but members of the choir lack mastery of Hebrew to ‘know’ exactly what they are saying/singing… The book was titled in English “A Merry Choir” – in Hebrew מקהלה עליזה . See if you can find a copy in a used book store, it is priceless and apparently out-of-print – well worth the search. If not, they may have a copy at Tel Aviv Amenu Museum’s music department – write them and see if they can send it to you. Or – if you will contact me via Whatsapp – (972) 546872768 or via my email – I will try and find the book (it is not where it ‘should be’ so I have to search) and I will photograph the score with my cell and send to you as an attachment. Best, Daniella Ashkenazy – Kfar Warburg.

שלום שמעון!

לא שכחתי אותך. עזבתי את ישראל בפברואר 1998 כדי להביא את בני האוטיסט לקבל את העזרה המקצועית שלא הייתה קיימת אז בישראל. זה סיפור מאוד עצוב וטרגי, אבל אני הייתי היחיד עם ביצים שהביא אותו והייתי הורה יחיד בשבילו במשך חמישה חודשים. הוא היה אז בן 9. כעת הוא בן 36 ומתפקד באופן עצמאי. נתתי לו הזדמנות לעתיד נורמלי. בטח, אבות כולם חרא, אומרים הפמינציות, אבל כולם צריכים לעבוד כמטרות במטווחי רובה!

משה קונג

(Maurice King)

Thank you for this wonderful remembrance of Herman Zalis. My late father, Henry Wahrman, was one of his students. Note the correct spelling of his name for future reference. Thank you again for sharing this.

Tirza Wahrman (Mitlak)

amazing zchuso yagein aleinu, he wrote the famous niggun Lefichuch that is sung in almost every Israeli Yeshiva

My grandmother, Rose Ziperson, wrote the words to his music for a song called Main Shtetele, which he produced. I have the sheet music!