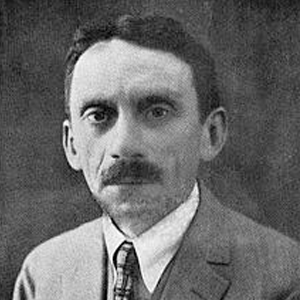

(1876–1927), Hebrew and Yiddish essayist and short-story writer; political and social activist. Born in Mszczonów and raised in a strict Hasidic milieu, Hersh Dovid Nomberg moved to Warsaw at age 21 to gain a secular education; he settled there with the help of a socialist organization. Nomberg taught himself Russian, Polish, and German and experienced a philosophical crisis as a result of his encounter with Haskalah and European literature. Convinced that Orthodoxy was outmoded, he chose a bohemian lifestyle and left his wife and young son.

Nomberg was close to Y. L. Peretz and remained a loyal disciple and skilled interpreter of his writing and philosophy until his own death. Under Peretz’s influence, Nomberg began to write in Yiddish in addition to Hebrew. He and his Warsaw flatmates Avrom Reyzen and Sholem Asch formed the “triad” of leading young Yiddish writers. Beginning in 1900, he published poems, novellas, short stories, and literary criticism in Hebrew and Yiddish periodicals, often translating his own works from one language to the other. His first publication was the Yiddish poem “Der novi” (The Prophet) in Der yud (1900); his first story, “Lailah ‘al-pene ha-sadeh” (Evening in the Field), appeared in Hebrew in Ha-Dor (1901). His early novellas Fun a poylisher yeshive (From a Polish Yeshiva; 1901) and Der rov un zayn zun (The Rabbi and His Son), based loosely on his own experiences, earned him critical praise. He served as editor of Ha-Tsofeh in 1904–1905.

Between 1905 and 1907 Nomberg traveled to Germany, France, and Switzerland, and spent time in Riga. He worked for various Yiddish newspapers and journals in Vilna until 1908, at which point he returned to Warsaw. Between 1908 and 1910 he published widely, including the novellas Di kursistke (a term denoting a female university student), Dos shpil in libe (The Play at Love), and Tsvishn berg (In the Mountains).

Nomberg transplanted the figure of the talush (a deracinated, alienated individual) from Hebrew to Yiddish literature. His moody prose, best illustrated by his psychoanalytical tale “Fligelman” (1903), depicts intellectual pessimists disheartened by contemporary Jewish life but incapable of taking decisive action to change their situations. The title character was designated by critics such as Zalmen Reyzen and Yosef Ḥayim Brenner as the archetype of the Nombergian hero and a model for contemporary Hebrew literature. Critics also noted Nomberg’s ironic condescension to his conflicted, passive male figures, contrasted with his portrayal of spirited, aggressive, and erotic female characters. Though debilitated by a chronic lung condition, Nomberg, unlike his heroes, threw himself with restless body and spirit into social and political causes.

From 1908 on, Nomberg was one of the most active champions of Yidishizm (Yiddishism; a term he coined): he campaigned for it in his writing, on lecture tours, and by recruiting young talent to contribute to the Jewish “national renaissance” then underway in the cultural and political spheres. At the 1908 Yiddish language conference in Czernowitz, it was he who proposed the compromise formula calling for recognition of Yiddish as a (but not the) national language of the Jewish people. Beginning in 1909 in Der fraynd, he published journalistic and critical essays about literature and culture each Friday under the title Vokhndike shmuesn(Weekly Chats). In 1911, Nomberg returned from a visit to the United States, and became Peretz’s closest associate in the Hazomir choral society. With the theater critic Alexander Mukdoyni, he encouraged the Yidishe Teater-gezelshaft to combat the prevalence of shund(“trash”) and strove to establish a Yiddish art theater in Warsaw. By the outbreak of World War I, though, he had almost entirely ended his ties to the stage (his 1913 play Di mishpokhe [The Family] is an exception). Writing in Haynt from 1912, he devoted himself to the social and political questions of Jewish life in Poland and elsewhere.

During the German occupation of Poland in World War I, Nomberg became active in the Yiddish secular school movement and also played an important role in founding the Association of Jewish Writers and Journalists, for which he served as president from 1925 through 1927. He originated the term Folkism and was one of the chief organizers of the Folkspartey in 1916, whose cause of national cultural autonomy he championed in the Warsaw daily Der moment.He served as its delegate to the Sejm in 1919–1920 but gradually retreated from party activities, preferring to travel and write. He also wrote about social and political issues for the Jewish press in Polish, during World War I in Głos Żydowski and in the 1920s in Nasz Przegląd.

In 1922–1923, Nomberg visited Argentina, where Jewish immigrants impressed him with their idealism and attachment to Yiddish culture in contrast to their counterparts in the United States. He raised money there for the CYSHO (TSYSHO) schools and helped to organize a Yiddish writers association in Buenos Aires. He traveled in 1924 to Palestine, where he marveled at the idealism of the pioneers despite his objections to Zionism. In 1926 he again visited the United States and the Soviet Union, whose Jewish colonization programs he publicly supported.

10 thoughts on “Kaminos”

Was Nicholas related to Alexander Saslavsky who married Celeste Izolee Todd?

Anyone have a contact email for Yair Klinger or link to score for Ha-Bayta?

wish to have homeland concert video played on the big screen throughout North America.

can organize here in Santa Barbara California.

contacts for this needed and any ideas or suggestions welcomed.

Nat farber is my great grandpa 😊

Are there any movies or photos of max kletter? His wife’s sister was my stepmother, so I’m interested in seeing them and sharing them with his wife’s daughter.

The article says Sheb recorded his last song just 4 days before he died, but does not tell us the name of it. I be curious what it was. I’d like to hear it.

Would anyone happen to know where I can find a copy of the sheet music for a Gil Aldema Choral (SATB) arrangement for Naomi Shemer’s “Sheleg Al Iri”. (Snow on my Village)?

Joseph Smith

Kol Ram Community Choir, NYC

שלום שמעון!

לא שכחתי אותך. עזבתי את ישראל בפברואר 1998 כדי להביא את בני האוטיסט לקבל את העזרה המקצועית שלא הייתה קיימת אז בישראל. זה סיפור מאוד עצוב וטרגי, אבל אני הייתי היחיד עם ביצים שהביא אותו והייתי הורה יחיד בשבילו במשך חמישה חודשים. הוא היה אז בן 9. כעת הוא בן 36 ומתפקד באופן עצמאי. נתתי לו הזדמנות לעתיד נורמלי. בטח, אבות כולם חרא, אומרים הפמינציות, אבל כולם צריכים לעבוד כמטרות במטווחי רובה!

משה קונג

(Maurice King)

Thank you for this wonderful remembrance of Herman Zalis. My late father, Henry Wahrman, was one of his students. Note the correct spelling of his name for future reference. Thank you again for sharing this.

Tirza Wahrman (Mitlak)

amazing zchuso yagein aleinu, he wrote the famous niggun Lefichuch that is sung in almost every Israeli Yeshiva