The Israeli statesman Abba Eban, who has died aged 87, used words, with fluency and accuracy, as his most potent weapons. It was Eban who, in 1978, said of the Palestine Liberation Organisation’s Yasser Arafat that he “never missed an opportunity to miss an opportunity”.

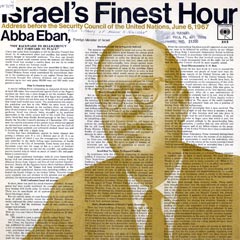

Eban first came to global attention three decades earlier, when he rose to address the General Assembly of the United Nations on May 5 1949. He was already a familiar figure to many of the delegates, having given an effective speech to the Security Council the previous July. On this occasion his widely reported two hour appeal for the provisional government of the new state of Israel to be recognised by the UN, and accepted as a member, was given major coverage, and his delivery had journalists and commentators reaching for superlatives. In the United States he became a world figure overnight, and during subsequent years it was in that country that he continued to evoke the greatest admiration.

In spite of the service he rendered over the years to his adopted country Israel, his very British appearance, Oxbridge accent and instinctive elitism set him uneasily apart from the great majority of Israeli citizens. The late-arriving Sephardic population could not identify itself with a man who seemed to be a consummately patrician Englishman. And in the end, the voters turned against one of their wisest, most benevolent and effective founding fathers.

Eban started as a brilliant scholar and would probably have been happy to spend his life as a highly respected professor writing books, a figure like Sir Isaiah Berlin, probably staying in Cambridge. Or he might have been successful in British politics. At Queens’ College, Cambridge, he took a triple first in oriental languages, outstripping all comers in Hebrew, Arabic and Persian. The following year, in 1938, he was appointed as a resident fellow and tutor at Pembroke College.

He was recruited by British intelligence and brought to the attention of Winston Churchill, who picked him for a secret mission to Egypt to discuss ways in which the Arab nations could be involved on the British side in the war that was just beginning. In 1942 he became a liaison officer at allied headquarters in Jerusalem, his responsibility being mainly to communicate with the Jewish population and to recruit for the army. He also had much to do with the Jewish Brigade.

In 1944 he was chief instructor at the Middle East Arab Centre in Jerusalem, but left to join the Jewish Agency in 1946, thereafter becoming fully involved with the Zionist cause. He was a member of the first provisional government, and always the most moderate voice at a time of conflict, uncertainty and confusion. In 1947 he was sent as head of a special commission to the UN. The following year Israel became a fait accompli, having declared itself on May 14 to be an independent state.

Eban’s great speech to the entire General Assembly was as much aimed at the American public and world opinion as at the assembled delegates, and it led to Israel’s admission to the UN. Britain recognised Israel in 1950. Eban then became the Israeli delegate to the UN and retained that post until 1959, becoming vice-president of the General Assembly in 1953. But at the same time he was Israeli ambassador (1950-1959) to the US, his country’s most important diplomatic posting, which did not stop him being active in Israeli politics as a member of the Labour party, as a writer and a public speaker whose words carried great influence.

Back in Israel he was elected to the Knesset and served there from 1959 to 1988. He was minister without portfolio (1959-60), education and culture minister (1960-63) and deputy prime minister (1963-66). He occupied other posts, but was most influential as foreign minister (1966-74).

He was always the Israeli minister who was best able to understand and talk to the Arabs, always opposed to war except in extreme necessity and equally to repression; in a state where the hawks became ever more numerous and vocal, he remained a dove, urging moderation. In 1988 he was finally rejected by the Labour party’s new, broadened selection committee for a new parliamentary candidacy.

Some attributed his fallout with Labour to the report produced while he was chairing the Knesset’s foreign affairs and defence committee. This suggested that the then Labour party leader Shimon Peres should have shared blame for the Jonathan Pollard espionage scandal with the then Likud leader Yitzhak Shamir. Pollard was recruited as an Israeli spy while working for the US navy. Eban had also protested at police brutality, saying that he wanted no part of a government that used sticks to beat young boys; worse excesses were to follow.

From that time he took advantage of his great American popularity to lecture at universities and to audiences throughout the US. His books were very successful there, especially his volume of speeches, Voice of Israel (1957), published when he was still ambassador.

Abba Eban was not his original name. His father was Avram Solomon, who as a young man went out to South Africa from England with his wife Alida Sacks (the aunt of Oliver Sacks), and died there at the age of 23, having fathered two children. His mother returned to London and remarried a radiologist who gave Eban as the family name to his step-children and brought them up together with the two children that he subsequently fathered. The two elder children were not told their real name until later. Abba is a hebraic version of Aubrey, which he took when he threw in his lot with Israel. He was known as Aubrey by old friends and family.

Brought back to England from Cape Town as a small child, Aubrey Eban attended St Olave’s and St Saviour’s school in Southwark where he excelled in English and classics. At the age of 14 he took part in a school debate. The headmistress praised him for his delivery and the way he had organised his thinking, but complained to his mother that he had been dishonest in not naming his sources, because at that age he could never have thought up such arguments on his own. His mother challenged the headmistress to organise another debate at short notice and to let Aubrey take part without knowing the subject in advance.

He distinguished himself equally well on that occasion and was vindicated. The family was not affluent and had four children to educate, but his schooling and subsequent academic career was made possible by the brilliance that enabled him to win every scholarship for which he sat.

He remained a liberal, humanitarian and practical intellectual all his life. He had the rare gift of objectivity, of rational assessment of the past and present and a world view that no other Israeli could claim. Indeed all his books, in spite of his passionate belief in his country’s cause, exhibit the cool and objective outlook of a wise statesman, caring for the wellbeing of all people, in all parts of the world, without prejudgment, accurately following cause and effect to explain the international events of the second half of the 20th century.

This is particularly true of what might well be his most significant book, The New Diplomacy (1983), which looks at the course of events since 1940 and especially after the San Francisco UN conference of April 1945: the allied powers believed at the time that it was possible permanently to organise a world that would never again see war or aggression. He underlined the folly of that assumption and of many that have been made since.

The point of his book was to explain how modern history had changed in the post-war period, from diplomacy to summitry, thereby making the essential secrecy that had been characteristic of diplomacy in past centuries, where raisons d’état was an ambassador’s prime motivation, no longer possible; press intrusion and the right of a democratic public “to know” then superseded every precedent. Stalin had said that honest diplomacy was like dry water, and while lies might remain a diplomatic necessity, the real direction of policy could no longer be concealed for long. The role of the diplomat has been rendered obsolete by modern communications and the prevalence of top conferences and summitry, with world leaders meeting frequently and negotiating directly, although not very effectively. He regretted this.

Abba Eban, shamefully, is not even included in most British biographical dictionaries. He was one of the finest political philosophers of his century, and his long-term influence may rival his practical accomplishments in life.

His many publications include: The Toynbee Heresy (1955), Tide of Nationalism (1959), Israel In The World (1966), My People (1968), My Country (1972), An Autobiography (1978), The New Diplomacy (1983).

In 1945 he married Susan Ambache and had one son and one daughter.