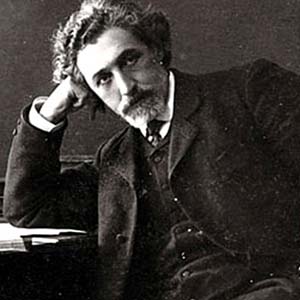

(1863–1920), Russian and Yiddish writer, ethnographer, and revolutionary activist. Shloyme Rapoport (known more commonly as S. [Semen Akimovich] An-ski) is most acclaimed for two Yiddish works: his play Der dibek: Tsvishn tsvey veltn (The Dybbuk: Between Two Worlds) and the Jewish Labor Bund’s anthem known as “Di shvue” (The Oath). He is also famous for landmark ethnographic expeditions that he led to Volhynia and Podolia in 1912–1914. Rapoport distinguished himself from other Yiddish writers of his generation by his successful career as a journalist in Russian, his intense involvement first with the Russian populist movement and then with the Socialist Revolutionary (SR) Party, and his professional interest in the social sciences. He was also known by the pseudonyms S. Vid’bin, Z. Sinanni, and S. Sinani.

Life

Rapoport was born in Chashniki and grew up in Vitebsk, in a family poorer than that of many contemporary writers. His mother, apparently separated from her husband, ran a tavern. Rapoport’s formal education stopped after heder, but he and his close friend Khayim Zhitlovski read Russian literature and criticism on their own. In his late teens, Rapoport left home. He worked as a tutor in Liozno (Bel., Liazna) until Jewish community leaders discovered that he was disseminating radical ideas; he was consequently dismissed in 1882. When he was 21, his first novel, Istoriia odnogo semeistva (History of a Family), was translated from Yiddish into Russian, and appeared in Voskhod (The Dawn; 1884).

As a populist, Rapoport believed that Russia’s rural population was central to the country’s future and that intellectuals needed to repay a moral debt to the poor, especially to peasants. Accordingly, when he lived in the Ekaterinoslav region in the 1880s, working alternately as a tutor and in the salt- and coal-mining industry, he collected workers’ songs and gave public readings to peasants and miners (he was arrested for these activities in 1888, but was released).

Rapoport’s literary career began in earnest after he traveled to Saint Petersburg in early 1892. There, the populist writer Gleb Uspensky introduced him to the editors of Russkoe bogatstvo (Russian Wealth), where he published stories and articles as S. An-ski, a name he would use for the rest of his life to sign his literary works and personal documents. An-ski spent his thirties and early forties (July 1892–December 1905) in Western Europe, where he continued to work for radical political and cultural causes and to write in Russian, and eventually also in Yiddish. He read broadly during those years in European literature and social theory, wrote articles about folklore, literature, and literacy in Russia and Europe, and planned a large synthetic work on folklore. Working part-time in Paris as a literary agent and as secretary to the revered Russian radical philosopher Petr Lavrov, An-ski became fascinated with European politics, especially the Dreyfus Affair, and met some of the Dreyfusards.

After Lavrov’s death in February 1900, An-ski married a French-Russian woman, but their relationship soon ended. Perhaps in the aftermath, he returned to writing in Yiddish with a translation of a Russian elegy. Having moved to Switzerland, he and Russian revolutionary Viktor Chernov founded a radical populist organization, the Agrarian Socialist League. In 1901, An-ski read Y. L. Peretz’s collected works and was impressed that Yiddish writing could be so modern; that same year at a Jewish Labor Bund event in Bern, he read a revolutionary poem in Yiddish, “Tsum Bund: In zaltsikn yam fun mentshlekhe trern” (To the Bund: In the Salty Sea of Human Tears), later published in Der idisher arbayter (The Jewish Worker; 1902) along with “Di shvue.”

An-ski went on to write considerable amounts of poetry and prose on Jewish themes in Russian and Yiddish. At the same time, with Yosef Ḥayim Brenner, he edited Kampf un kempfer (The Fight and the Fighters, 1904–1905), a Socialist Revolutionary journal in Yiddish. Unlike the more orthodox Marxist Social Democrats (SDs), the members of the SR Party focused more on peasants than on industrial workers and believed that terrorism was a legitimate revolutionary tactic. An-ski’s journal was presumably an attempt to reach out to Jews, who were usually more attracted to the Social Democrats.

After the revolution of 1905 led to the October Manifesto guaranteeing amnesty to radicals, An-ski returned to Russia and plunged into Jewish and Russian politics. In February and March 1906, he debated Simon Dubnow in the pages of Voskhod, defending the dedication of Jews to the revolution; in 1909, he debated Zhitlovski and others in Dos naye lebn (The New Life, published in New York), arguing for limiting Christian imagery in Jewish literature; and in 1910, he debated Shmuel Niger and others in Evreiskii mir (Jewish World), defending his trilingual vision of modern Jewish literature.

While writing and editing for a general Russian audience, An-ski also became involved in the growing world of Jewish publishing, editing or founding Evreiskii mir, and contributing to Evreiskaia starina (Jewish Heritage), the Evreiskaia entsiklopediia (Jewish Encyclopedia), Evreiskoe obozrenie (Jewish Views), and Molodoe evreistvo (Jewish Youth). From 1908 to 1918, he traveled through the empire, giving lectures to proliferating Jewish cultural organizations on mainly Jewish cultural topics. He was simultaneously active in SR politics, attending illegal congresses, publishing the book Chto takoe anarkhizm? (What is Anarchism?) and writing revolutionary plays. Arrested in January 1907 for disseminating revolutionary propaganda, he was again released. In 1908, he married Esther Glezerman, a much younger Jewish woman, but the marriage soon foundered.

An-ski’s interest in Russian folklore had expanded during his European years to include Jewish folklore. Starting in 1907, he systematically collected examples from Jewish communities and published an article, “Evreiskoe narodnoe tvorchestvo” (Jewish Folk Art), in Perezhitoe (The Past; 1908). Whereas his contemporaries in the Russian Empire, such as Ḥayim Naḥman Bialik and Yehoshu‘a Ḥana Ravnitski, were intrigued by the Hebrew folklore of the Talmud and Midrash, An-ski had a populist’s impulse to collect oral texts from living sources. With funding from sources including Baron Vladimir Gintsburg, he organized an ethnographic expedition to the Pale of Settlement. He and his team (Solomon Iudovin, Yoel Engel, Avrom Rekhtman, and others) traveled through Volhynia and Podolia in the summers of 1912–1914 and gathered 2,000 photographs, 1,800 folktales, 1,500 folk songs, 1,000 melodies, 100 historical documents, and 500 manuscripts. They also purchased 700 sacred objects for 6,000 rubles, and recorded 500 wax cylinders of folk music.

Apparently inspired by the expedition’s findings, An-ski drafted The Dybbuk in Russian in late 1913. Although it was accepted by Konstantin Stanislavsky for the Moscow Art Theater’s 1917 season, plans for production changed with the February Revolution. The play was not performed until December 1920, after An-ski’s death, by the Vilner Trupe in Warsaw in the author’s own Yiddish version, and in 1922 by the Habimah Theater in Moscow in Bialik’s Hebrew translation.

From the start of World War I through 1917, An-ski worked for the Evreiskii Komitet Pomoshchi Zhertvam Voiny (Jewish Committee for the Relief of War Victims; EKOPO), distributing aid to Jews in war-torn Poland, Galicia, and Bucovina. He also turned his Russian diary into a Yiddish memoir of his experiences, Khurbn Galitsye (The Destruction of Galicia; 1920). After February 1917, An-ski was elected to the All-Russian Constituent Assembly as a Socialist Revolutionary, representing Vitebsk; following the Bolshevik takeover, he fled to Vilna in September 1918.

After his friend A. Vayter was killed in a pogrom in April 1919, An-ski left for Warsaw. He spent his last months translating his Russian works into Yiddish and planning a collection of his complete works in Yiddish. He died of a heart attack the day after attending an organizational meeting for a Warsaw Jewish Ethnographic Society.

Major Achievements

An-ski’s ethnographic scholarship is more significant than the balance of his nonfiction. It includes two monographs on peasant literacy, Ocherki o narodnoi literature (Sketches on Folk Literacy; 1892/1894) and Narod i kniga (The Folk and the Book; 1913), articles on Jewish folklore in Russian and Yiddish, such as “Evreiskoe narodnoe tvorchestvo” (Jewish Folk Art; 1908), Der mensh (Man [the questionnaire used by the expedition]; 1914), and Al’bom evreiskoi khudozhesdvennoi stariny (Album of the Jewish Artistic Heritage; published only after the fall of the Soviet Union).

Although his early work presents a bleak, typically populist picture of traditional societies threatened by modernity, An-ski’s later works in both Russian and Jewish contexts highlight the creativity that can result from encounters between cultures or between new and old texts. An-ski never formally analyzed the materials gathered on the expedition, although he refers to them in Khurbn Galitsye.

The prose that An-ski produced in Russian and Yiddish has been criticized as stylistically flat, but the content remains compelling. His depictions in the novel Pionery/Pionern (Pioneers; 1904–1905) of yeshiva boys who dream of revolution are poignant and ironic; his portrayal in the novella V novom rusle (On a New Course; 1907) of the revolutionary turmoil in a single city reveals fissures in the radical movements. Stories such as “Golodnyi” (Hungry; 1892) and “Mendel Turok” (Mendel the Turk; 1892) sensitively present Jewish characters torn between assimilation and tradition. In Khurbn Galitsye, his longest prose work, he illustrates and analyzes his own paradoxically dual affiliation to Russian and Jewish cultures against a background of horrifying wartime suffering.

Much of An-ski’s poetry and drama served ideological purposes. His one-act plays about the radical movement were popular among his fellow émigrés before 1905; they were published illegally in Russia after 1905 and republished after 1917. The revolutionary Yiddish verse for which he remains known—including “Tsum Bund” and “Di shvue”—emerged from his study of French revolutionary songs and is indebted to them. Other poems—of which “Ashmedai” (a narrative poem about a devil’s divorce, inspired by Peretz’s “Monish”) is the most successful—are folkloric stylizations that attest to Rapoport’s ability to combine neo-Hasidism and radicalism.

In his best-known folkloric stylization, The Dybbuk, the yeshiva student Khonen and the virtuous Leah were promised to each other in marriage before their birth, but now Leah’s father Sender wants to find her a rich husband instead. Khonen tries to use Kabbalah to make Leah his bride but dies after invoking the devil. Khonen’s soul enters Leah’s body as a dybbuk. Rebbe Azriel presides at a trial between Sender and Khonen’s dead father, Nisn, after which he succeeds in exorcising the dybbuk from Leah’s body. In the denouement, Khonen’s spirit returns to her soul and the lovers die united. The play was a remarkable box office success that has been translated into dozens of languages. Nonetheless, other writers have consistently criticized it for being melodramatic, middlebrow, insufficiently Zionist, excessively influenced by mystical Russian symbolist theater, and so loaded down with ethnographic detail that it is almost impossible to stage.

An-ski differs from the Yiddish writers of his generation for linguistic, political, and scholarly reasons. Although Sholem Aleichem and Mendele Moykher-Sforim were fluent in Russian, they published little in it; An-ski is unusual in having made a successful career as a Russian writer before turning to Yiddish. His dual linguistic allegiance may account for his stylistic poverty, but comparison of the Russian and Yiddish versions of individual texts reveals the subtle variations in his self-presentation to different audiences. His primarily Russian orientation may account for his strikingly ironic, rather than satiric, depictions of Jewish life. Whereas many Yiddish writers were also radicals, few joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party, with its orientation toward peasants. Undoubtedly An-ski’s foundations in Russian populism and his writings about peasant culture led to his equally detailed and politically motivated study of Jewish traditional culture. His remarkable letters reveal his strong emotions, sensitivity to the problems of others, and powers of observation. He impressed his contemporaries with his passion, his idealism, and his ability to give himself completely to constituencies and causes that others saw as mutually exclusive.

10 thoughts on “Kaminos”

Was Nicholas related to Alexander Saslavsky who married Celeste Izolee Todd?

Anyone have a contact email for Yair Klinger or link to score for Ha-Bayta?

wish to have homeland concert video played on the big screen throughout North America.

can organize here in Santa Barbara California.

contacts for this needed and any ideas or suggestions welcomed.

Nat farber is my great grandpa 😊

Are there any movies or photos of max kletter? His wife’s sister was my stepmother, so I’m interested in seeing them and sharing them with his wife’s daughter.

The article says Sheb recorded his last song just 4 days before he died, but does not tell us the name of it. I be curious what it was. I’d like to hear it.

Would anyone happen to know where I can find a copy of the sheet music for a Gil Aldema Choral (SATB) arrangement for Naomi Shemer’s “Sheleg Al Iri”. (Snow on my Village)?

Joseph Smith

Kol Ram Community Choir, NYC

שלום שמעון!

לא שכחתי אותך. עזבתי את ישראל בפברואר 1998 כדי להביא את בני האוטיסט לקבל את העזרה המקצועית שלא הייתה קיימת אז בישראל. זה סיפור מאוד עצוב וטרגי, אבל אני הייתי היחיד עם ביצים שהביא אותו והייתי הורה יחיד בשבילו במשך חמישה חודשים. הוא היה אז בן 9. כעת הוא בן 36 ומתפקד באופן עצמאי. נתתי לו הזדמנות לעתיד נורמלי. בטח, אבות כולם חרא, אומרים הפמינציות, אבל כולם צריכים לעבוד כמטרות במטווחי רובה!

משה קונג

(Maurice King)

Thank you for this wonderful remembrance of Herman Zalis. My late father, Henry Wahrman, was one of his students. Note the correct spelling of his name for future reference. Thank you again for sharing this.

Tirza Wahrman (Mitlak)

amazing zchuso yagein aleinu, he wrote the famous niggun Lefichuch that is sung in almost every Israeli Yeshiva