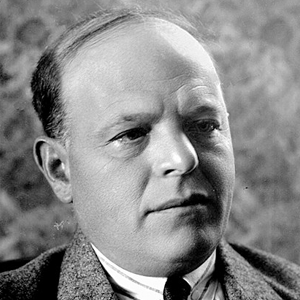

Haim Nahman Bialik (Hebrew: חיים נחמן ביאליק; January 6, 1873 – July 4, 1934), also Chaim or Hayim, was a Jewish poet who wrote primarily in Hebrew but also in Yiddish. Bialik was one of the pioneers of modern Hebrew poetry. He was part of the vanguard of Jewish thinkers who gave voice to the breath of new life in Jewish life. Bialik ultimately came to be recognized as Israel’s national poet.

Bialik was born in Ivnitsa, Zhitomir district, Volhynian Governorate in the Russian Empire to Itzik-Yosef Bialik, a scholar and businessman from Zhitomir, and his wife Dinah-Priveh. He had older brother Sheftel (born in 1862) and sister Chenya-Ides (born in 1871), as well as a younger sister Blyuma (born in 1875). When Bialik was still a child, his father died. In his poems, Bialik romanticized the misery of his childhood, describing seven orphans left behind—though modern biographers believe there were fewer children, including grown step-siblings who did not need to be supported. Be that as it may, from the age 7 onwards Bialik was raised in Zhitomir by his Orthodox grandfather, Yankl-Moishe Bialik.

In Zhitomir he received a traditional Jewish religious education, but also explored European literature. At the age of 15, inspired by an article he read, he convinced his grandfather to send him to the Volozhin Yeshiva in Lithuania, to study at a famous Talmudic academy under Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin, where he hoped he could continue his Jewish schooling while expanding his education to European literature as well. Attracted to the Jewish Enlightenment movement (Haskala), Bialik gradually drifted away from yeshiva life. Poems such as HaMatmid (“The Talmud student”) written in 1898, reflect his great ambivalence toward that way of life: on the one hand admiration for the dedication and devotion of the yeshiva students to their studies, on the other hand a disdain for the narrowness of their world.

At 18 he left for Odessa, the center of modern Jewish culture in the southern Russian Empire, drawn by such luminaries as Mendele Mocher Sforim and Ahad Ha’am. In Odessa, Bialik studied Russian and German language and literature, and dreamed of enrolling in the Modern Orthodox Rabbinical Seminary in Berlin. Alone and penniless, he made his living teaching Hebrew. The 1892 publication of his first poem, El Hatzipor “To the Bird,” which expresses a longing for Zion, in a booklet edited by Yehoshua Ravnitzky (a future collaborator), eased Bialik’s way into Jewish literary circles in Odessa. He joined the Hovevei Zion movement and befriended Ahad Ha’am, who had a great influence on his Zionist outlook.

In 1892 Bialik heard news that the Volozhin yeshiva had closed and returned home to Zhitomir to prevent his grandfather from discovering that he had discontinued his religious education. He arrived to discover his grandfather and his older brother both on their deathbeds. Following their deaths, Bialik married Manya Averbuch in 1893. For a time he served as a bookkeeper in his father-in-law’s lumber business in Korostyshiv, near Kiev. But when this proved unsuccessful, he moved in 1897 to Sosnowiec, a small town in Zaglembia, southern Poland, which was then part of the Russian Empire, near the border with Prussia and Austria. In Sosnowiec, Bialik worked as a Hebrew teacher and tried to earn extra income as a coal merchant, but the provincial life depressed him. He was finally able to return to Odessa in 1900, having secured a teaching job.

Bialik’s first visit to the US was to Hartford, CT, where he stayed with Cousin Raymond Bialeck and his family. His closest living relatives in the US include Hal Bialeck, Alison Bialeck and Richard Bialeck. He is the uncle of Mayim Bialik’s great-great-grandfather.

For the next two decades, Bialik taught and continued his activities in Zionist and literary circles, as his literary fame continued to rise. This is considered Bialik’s “golden period”. In 1901 his first collection of poetry was published in Warsaw, and was greeted with much critical acclaim, to the point that he was hailed “the poet of national renaissance.” Bialik relocated to Warsaw briefly in 1904 as literary editor of the weekly magazine HaShiloah founded by Ahad Ha’am, a position he served for six years.

In 1903 Bialik was sent by the Jewish Historical Commission in Odessa to interview survivors of the Kishinev pogroms and prepare a report. In response to his findings Bialik wrote his epic poem In the City of Slaughter, a powerful statement of anguish at the situation of the Jews. Bialik’s condemnation of passivity against anti-Semitic violence is said to have influenced the founding Jewish self-defense groups in the Russian Empire, and eventually the Haganah in Palestine. Bialik visited Palestine in 1909.

In the early 20th century, Bialik founded with Ravnitzky, Simcha Ben Zion and Elhanan Levinsky, a Hebrew publishing house, Moriah, which issued Hebrew classics and school texts. He translated into Hebrew various European works, such as Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell, Cervantes’ Don Quixote, and Heine’s poems; and from Yiddish S. Ansky’s The Dybbuk.

Throughout the years 1899–1915, Bialik published about 20 of his Yiddish poems in different Yiddish periodicals in the Russian Empire. These poems are often considered to be among the best achievements of modern Yiddish poetry of that period. In collaboration with Ravnitzky, Bialik published Sefer HaAggadah (1908–1911, The Book of Legends), a three-volume edition of the folk tales and proverbs scattered through the Talmud. For the book they selected hundreds of texts and arranged them thematically. The Book of Legends was immediately recognized as a masterwork and has been reprinted numerous times. Bialik also edited the poems of the medieval poet and philosopher Ibn Gabirol. He began a modern commentary on the Mishnah, but only completed Zeraim, the first of the six Orders (in the 1950s, the Bialik Institute published a commentary on the entire Mishnah by Hanoch Albeck, which is currently out of print). He additionally added several commentaries on the Talmud.

In Odessa, namely in 1919, he was also able to found the Dvir publishing house, which would later become famous. This publishing house, now based in Israel, is still in existence, but is now known as Kinneret Zmora-Bitan Dvir after Dvir was purchased by the Zmora-Bitan publishing house in 1986, which later fused with Kinneret as well.

Bialik lived in Odessa until 1921, when the Moriah publishing house was closed by Communist authorities, as a result of mounting paranoia following the Bolshevik Revolution. With the intervention of Maxim Gorki, a group of Hebrew writers were given permission by the Soviet government to leave the country. While in Odessa he had befriended the soprano Isa Kremer whom he had a profound influence on. It was through his influence that she became an exponent of Yiddish music on the concert stage; notably becoming the first woman to concertize that music.

Bialik wrote several different modes of poetry. He is perhaps most famous for his long, nationalistic poems, which call for a reawakening of the Jewish people. Bialik had his own awakening even before writing those poems, arising out of the anger and shame he felt at the Jewish response to pogroms. In his poem “Massa Nemirov”, for example, Bialik excoriated the Jews of Kishinev who had allowed their persecutors to wreak their will without raising a finger to defend themselves.

However no less effective are his passionate love poems, his personal verse, or his nature poems. Last but not least, Bialik’s songs for children are a staple of Israeli nursery life. From 1908 onwards, he wrote mostly prose.

By writing his works in Hebrew, Bialik contributed significantly to the revival of the Hebrew language, which before his days existed primarily as an ancient, scholarly tongue. His influence is felt deeply in all modern Hebrew literature. The generation of Hebrew language poets who followed in Bialik’s footsteps, including Jacob Steinberg and Jacob Fichman, are called “the Bialik generation”.

To this day, Bialik is recognized as Israel’s national poet. Bialik House, his former home at 22 Bialik Street in Tel Aviv, has been converted into a museum, and functions as a center for literary events. The municipality of Tel Aviv awards the Bialik Prize in his honor. Kiryat Bialik, a suburb of Haifa, and Givat Hen, a moshav bordering the city of Raanana, are named after him. He is the only person to have two streets named after him in the same Israeli city – Bialik Street and Hen Boulevard in Tel Aviv. There is also Bialik Hebrew Day School in Toronto, ON, Canada; Bialik High School in Montreal, QC, Canada; and a cross-communal Jewish Zionist school in Melbourne called Bialik College. In Caracas, Venezuela, the largest Jewish community school is named Herzl-Bialik. Also in Rosario, Argentina the only Jewish school is named after him.

Bialik’s poems have been translated into at least 30 languages, and set to music as popular songs. These poems, and the songs based on them, have become an essential part of the education and culture of modern Israel.

Bialik wrote most of his poems using “Ashkenazi” pronunciation, while modern Israeli Hebrew uses the Sephardi pronunciation. Consequently, Bialik’s poems are rarely recited in the meter in which they were written.

Bialik died in Vienna, Austria, on July 4, 1934, following a failed prostate operation. He was buried in Tel Aviv; a large mourning procession followed from his home on the street named after him, to his final resting place.

10 thoughts on “Kaminos”

Was Nicholas related to Alexander Saslavsky who married Celeste Izolee Todd?

Anyone have a contact email for Yair Klinger or link to score for Ha-Bayta?

wish to have homeland concert video played on the big screen throughout North America.

can organize here in Santa Barbara California.

contacts for this needed and any ideas or suggestions welcomed.

Nat farber is my great grandpa 😊

Are there any movies or photos of max kletter? His wife’s sister was my stepmother, so I’m interested in seeing them and sharing them with his wife’s daughter.

The article says Sheb recorded his last song just 4 days before he died, but does not tell us the name of it. I be curious what it was. I’d like to hear it.

Would anyone happen to know where I can find a copy of the sheet music for a Gil Aldema Choral (SATB) arrangement for Naomi Shemer’s “Sheleg Al Iri”. (Snow on my Village)?

Joseph Smith

Kol Ram Community Choir, NYC

שלום שמעון!

לא שכחתי אותך. עזבתי את ישראל בפברואר 1998 כדי להביא את בני האוטיסט לקבל את העזרה המקצועית שלא הייתה קיימת אז בישראל. זה סיפור מאוד עצוב וטרגי, אבל אני הייתי היחיד עם ביצים שהביא אותו והייתי הורה יחיד בשבילו במשך חמישה חודשים. הוא היה אז בן 9. כעת הוא בן 36 ומתפקד באופן עצמאי. נתתי לו הזדמנות לעתיד נורמלי. בטח, אבות כולם חרא, אומרים הפמינציות, אבל כולם צריכים לעבוד כמטרות במטווחי רובה!

משה קונג

(Maurice King)

Thank you for this wonderful remembrance of Herman Zalis. My late father, Henry Wahrman, was one of his students. Note the correct spelling of his name for future reference. Thank you again for sharing this.

Tirza Wahrman (Mitlak)

amazing zchuso yagein aleinu, he wrote the famous niggun Lefichuch that is sung in almost every Israeli Yeshiva